Written by: Dr. Jacquie Jacob, University of Kentucky

Raising chickens can be fun and educational for the entire family. Whether you are starting a new flock or adding to an existing one, a first task is to choose the chicken breed you want to raise.

A breed is a group of individuals with the same physical characteristics. Several breeds of chickens exist, and those breeds are further categorized into classes. A class is a group of breeds originating in the same geographical location. Five classes of chicken breeds are American, Asiatic, English, Mediterranean, and Continental. Breeds not included in these classes are included in the Any Other Standard Breed class.

There are many things to consider before selecting a chicken breed for your flock. The kind of chicken you select depends on whether you want meat, eggs, or exhibition poultry.

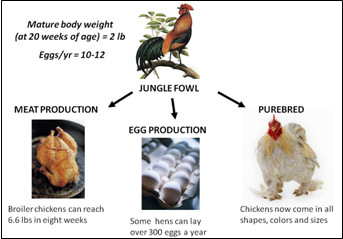

All breeds of chickens around today are descended from the Red Jungle Fowl of Southeast Asia. Generations of genetic selection have developed breeds specializing in specific characteristics, as illustrated in Figure 1. For example, the mature weight of the Red Jungle Fowl is only about 2 pounds, whereas today’s chicken breeds developed specifically for meat production can reach a market weight of 6.6 pounds in only eight weeks. Similarly, while the sexually mature Red Jungle Fowl hen lays 10 to 12 eggs during the breeding season, hens from chicken breeds developed specifically for egg production lay year round and can produce more than 300 eggs in a year. Moreover, chicken breeds now come in all shapes, sizes, and colors, making poultry exhibition an interesting and colorful experience.

MEAT PRODUCTION

Among meat-producing breeds (broiler chickens), nothing compares with the hybrid Cornish Cross (based on the Cornish crossed with the White Plymouth Rock) for fast growth and feed efficiency. These chickens can reach 4 to 5 pounds in six weeks or 6 to 10 pounds in eight to 12 weeks (see Figure 2). Of course, this growth level depends on management conditions, especially housing and nutrition. Cornish Cross chickens are not efficient egg producers because they must consume a large amount of feed just for body maintenance. Additionally, the inherent obesity of these chickens reduces their capacity to produce eggs.

Typically, broiler chickens do not do well in a pasture or free-range system. Consequently, many producers are opting for dual-purpose breeds. Dual-purpose breeds are those breeds of which the hens lay reasonably well and the males are large enough for meat production. Many of the American breeds originally were developed as dual-purpose breeds for small family farms. These include the Plymouth Rock, Rhode Island Red, New Hampshire, and Wyandotte and others. Dual-purpose breeds also exist in the Asiatic and English classes. The Asiatic breeds, which are large and have feathered feet, include the Brahma, Cochin, and Langshan. English breeds are characterized by their white skin, which is popular in Europe.

In Europe, a large market exists for slower-growing meat-type chickens. Some of these breeds have been imported into the United States and recently have become available for purchase. Typically, they are raised for 11 to 12 weeks and are, therefore, closer to sexual maturity at harvest than most commercial meat-type breeds. Because they are slower growing than the typical commercial broiler chicken, it is said that they have more flavor.

If you plan to produce meat-type chickens for the ethnic market, especially Asian consumers, choosing a dark-feathered, slower-growing breed is best. Although the Australorp was developed in Australia as an egg-producing breed, producers in many parts of the United States raise these chickens as meat birds for sale in live bird markets catering to the Asian market. Another breed popular in the Asian market is the silkie chicken. Silkie chickens, regardless of feather color, have black skin, black meat, and black bones. Some people believe that chicken soup made from the silkie chicken has medicinal properties.

EGG PRODUCTION

Chickens used solely for egg production are of two general types—those that produce white-shelled eggs and those that produce brown-shelled eggs. Most major primary breeds include strains that produce both white eggs and brown eggs.

The White Leghorn is the principal white egg producer. It can produce 260-plus eggs in 12 months. White Leghorns are lightweight birds that convert feed to eggs efficiently. Many strains of White Leghorns are available from the various primary breeders and their franchise hatcheries.

The brown egg layers, for the most part, are derived from American breeds, such as the Plymouth Rock, New Hampshire, or Rhode Island Red. These layers are somewhat lighter in weight than other breeds of the American class; thus, they require less feed for body maintenance. However, their feed requirements are greater than those of the White Leghorn, making production costs for brown eggs a little higher than for white eggs.

The commercial breeds of egg layers, however, tend to be flighty and high strung and are not good choices for small and backyard poultry flocks. An alternative is one of the sex-linked crosses that are bred for egg production and available at most hatcheries in the United States.

- The black sex-link cross (also known as the Rock Red) is produced by crossing a hen having a barred pattern in her feathers with a non-barred rooster. The male offspring typically have barred plumage like the mother, and the female offspring are a solid color, typically black. Black sex-link crosses are typically produced by crossing a Barred Plymouth Rock hen with a Rhode Island Red or New Hampshire Red rooster. At hatch, both sexes have black down, but the males can be identified by a white dot on the head.

- The red sex-link cross (also known as the Golden Comet, Gold Star, or Cinnamon Queen, depending on the specific cross used) is produced by a number of different crosses. A White Plymouth Rock hen with the silver factor (a gene on the sex chromosome that inhibits red pigmentation of feathers) is crossed with a New Hampshire male to produce the Gold Comet. A Silver Laced Wyandotte hen is crossed with a New Hampshire Red rooster to produce the Cinnamon Queen. Additional possible red sex-link cross combinations are the Rhode Island White hen with a Rhode Island Red rooster or a Delaware hen with a Rhode Island Red rooster. Males hatch out white and can feather out to pure white or to white with some black feathering, depending on the cross. Females hatch out buff or red, depending on the cross, and feather out buff or red.

All the most popular sex-link crosses produced for small flocks lay brown eggs. One sex-link cross that you can purchase for white egg production is the California White. It is the cross between a White Leghorn hen and a California Gray rooster. Basically, the California White is a commercial White Leghorn bred to be able to handle the conditions typical for small flocks, including areas with colder temperatures.

There are some additional options for egg-producing chickens. For white eggs, you can use the Minorca and Ancona breeds. For brown eggs, you can use the Australorp, Rhode Island Red, or New Hampshire Red breeds. Typically, hens of breeds with white ear lobes lay white eggs, and those of breeds with red ear lobes lay brown eggs. Exceptions to this rule are the Araucana and Ameraucana breeds, shown in Figure 3. The Araucana is a breed from South America that lays blue eggs. Genetically, the blue egg color is a dominant trait, and when the Araucana is crossed with other breeds, the result is a chicken that lays colored eggs. If the feather coloring of such a chicken meets the standards in the American Poultry Association (APA), the chicken usually is considered to be of the Ameraucana breed. If the feather coloring does not meet the standards of the APA, the chicken typically is referred to as an Easter Egger. Eggs produced by Ameraucana and Easter Egger hens vary from pink to green.

EXHIBITION

Poultry exhibition shows are popular in most states. Figure 4 shows examples of chickens that are popular for exhibition. The APA publishes the American Standard of Perfection, a publication that describes the ideal body types, colors, weights, and other characteristics of all recognized breeds and varieties. Chickens are judged according to these standards.

Most chicken breeds come in a standard size and a bantam size, although there are some bantam breeds for which there is no standard-size version. Bantams are typically one-quarter smaller than the size of their standard counterparts. Because of their smaller size, bantams are easier to handle, and they eat less feed and take up less space. Also, they lay smaller eggs. The American Bantam Association (ABA) produces a standard of perfection specifically for bantams.

The Society for the Preservation of Poultry Antiquities (SPPA) maintains a list of bantam and standard-size chickens that are in danger of disappearing and old, historically significant breeds for which documentation exists from before the era of the modern poultry show. Not all breeds on the list are considered rare. The organization designates a breed as rare if it deems that the breed is in need of more breeders to avoid genetic limitations and, ultimately, the disappearance of the breed. The list also includes breeds not listed in the APA and ABA standards of perfection but for which recorded histories exist.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Selecting the right chicken breed. Jacquie Jacob and Tony Pescatore, University of Kentucky.

Choosing a Chicken Breed: Eggs, Meat, or Exhibition. Doug Akers, Pete Akers, and Mickey Latour, Purdue University.

Match Your Need to the Right Breed: Choosing a Bird for the Home Flock. Robert Hawes and Richard Brzozowski, University of Maine.